Tackling Structural Racism Key to an Equitable Recovery in California

Data on unemployment filings in California reveals how the Black working class has been hardest hit by the Covid recession, underscoring the need for targeted, race-conscious recovery strategies.

By Eliza McCullough

While the economic crisis has affected a startling number of workers, workers of color and low-wage workers have been hit the hardest. In California, 8.7 million workers (nearly 45 percent of the labor force) have filed for unemployment insurance (UI) since the start of the pandemic in March 2020. But job displacement has varied dramatically by race and education, as illustrated by the California Policy Lab’s recent analysis of UI claims data. This post highlights how California’s Black workers are experiencing disproportionate unemployment in the Covid recession due to structural racism embedded in the labor market, and describes policy priorities to ensure an equitable recovery.

About 85 percent of California’s Black workforce has filed for unemployment at some point since March 15th, which is more than double the rate for White, Latinx, and Asian or Pacific Islander workers. This includes workers who filed for either regular UI or Pandemic Unemployment Assistance (PUA), a program created by the CARES Act to extend benefits to workers not usually eligible for regular UI.*

This unemployment crisis for Black workers in a time of economic contraction threatens to increase already-wide racial inequities in employment. Structural racism embedded in the US labor market has created barriers to employment for Black workers that predate the current recession, ranging from employer bias and discrimination to residential segregation and mass incarceration. Black workers are typically the group hardest hit by economic downturns and are often the last to recover, as evidenced during the Great Recession when Black workers disproportionately suffered from long-term unemployment. The current economic crisis has most negatively impacted the hospitality, retail, and tourism sectors, industries in which Black workers are concentrated due in large part to discriminatory public policies that restricted Black workers’ access to better-paying jobs in other industries (a phenomenon known as “occupational segregation”). As these service sectors have gone through massive lay-offs, Black employees have been subject to the “last hired, first fired” phenomenon in which low-wage positions are the first to be eliminated.

Further disaggregating the data by race and educational attainment, we see that racial inequities are particularly extreme among workers without four-year degrees. Workers of all races with lower education levels have been hardest hit by the Covid recession: More than half of California workers with a high school degree or less (who account for 38 percent of all workers in the state) have filed for unemployment since March 2020 compared to 13 percent of workers with a Bachelor’s degree or higher. But unemployment filings are particularly high for Black workers without post-secondary education: virtually all Black workers with a high school degree or less (99 percent) have filed for unemployment, along with 75 percent of Asian or Pacific Islander workers with this level of education, compared with 52 percent of White workers and 33 percent of Latinx workers.

Black workers are overrepresented in lower education groups due to deep-seated structures of racial exclusion which have created significant barriers to accessing higher education. Residential segregation, perpetuated by exclusionary zoning, has led to the concentration of low-income Black children in schools with inadequate resources, which researchers have found is the key driver of the educational achievement gap. Along with the rising costs of college, these barriers prevent many Black students from accessing post-secondary education. As middle-wage jobs have shrunk in recent decades, Black workers with no higher education have been pushed into low-wage, ‘flexible’ positions with minimal protections. These jobs have been most impacted by wage cuts, diminished hours, and layoffs during the current economic crisis.

Toward an Equitable Economic Recovery

Black workers and other workers of color are in dire need of increased supports in California and nationwide. Policymakers and business leaders must take action to address immediate economic needs as we enter the eleventh month of the pandemic. At the same time, they must launch forward-thinking, race-conscious strategies that lay the foundation for an equitable recovery and future economy. We recommend the following:

-

Continue expanded UI benefits and provide direct cash support. Additional UI payments under the Federal Pandemic Unemployment Compensation program should be increased back to $600/week (as provided from March to July). Additional and ongoing direct payments, such as the one-time $1,200 payments included in the CARES Act, could also provide a lifeline to unemployed workers and Black workers who are less likely to have adequate savings to fall back on.

-

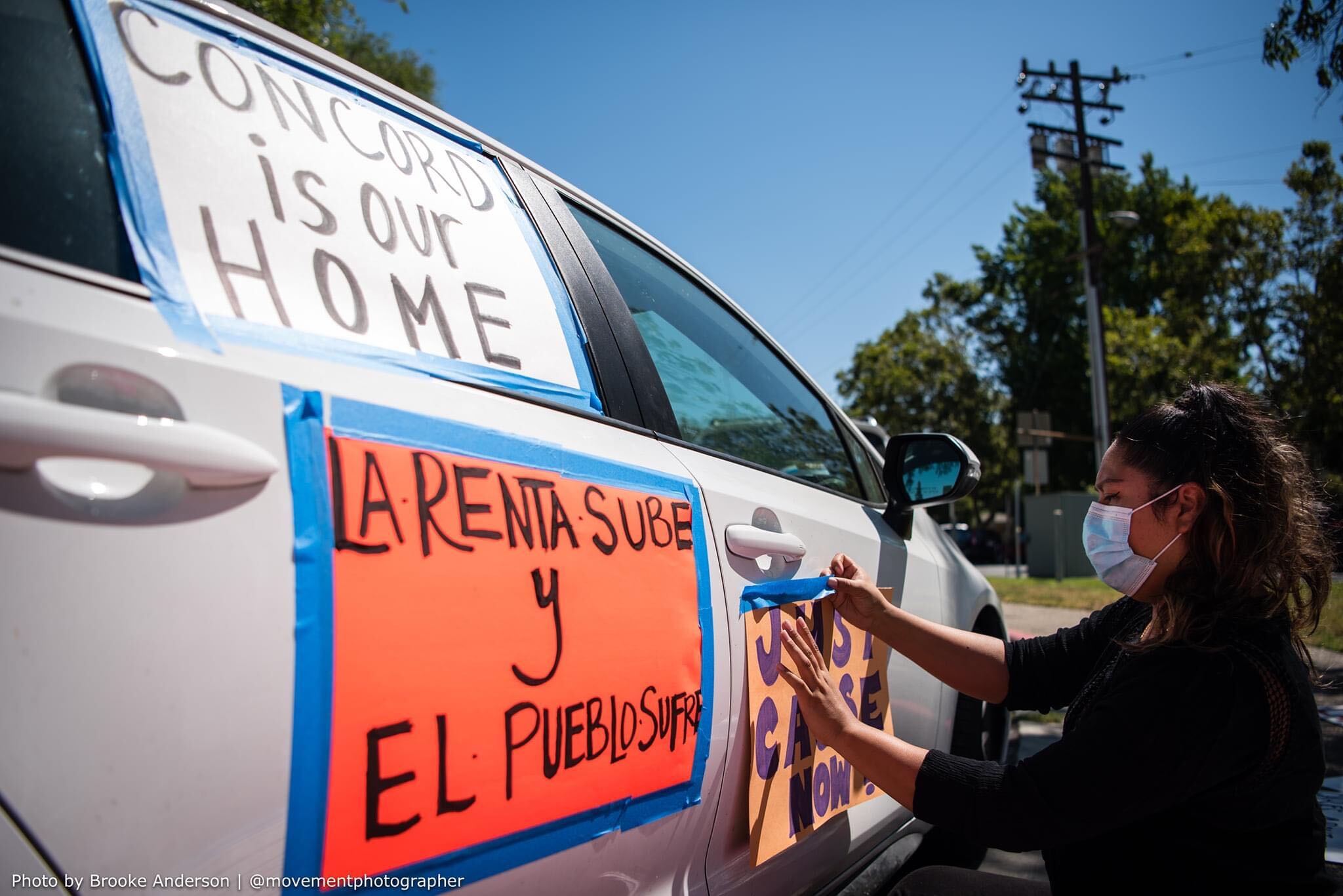

Prevent evictions and foreclosures and provide debt relief to Covid-impacted households. As unemployed workers are more likely to be behind on rent and California’s Black renters are already paying unaffordable rent, policymakers must extend eviction moratoriums and provide rent debt relief. Limited rental assistance funds should be targeted to the hardest-hit households, particularly those in predominantly Black neighborhoods and neighborhoods of color, to prevent displacement and homelessness.

-

Protect existing jobs. Multiple cities have passed legislation to ensure that laid-off workers in low-wage sectors can return to their former jobs. For example, Oakland’s Right to Recall policy requires employers in hospitality and travel to give laid-off workers priority when operations resume. Similar policies that protect jobs across sectors should also be implemented at the state and federal levels to ensure low-wage workers do not suffer from long-term joblessness or decreases in income and benefits.

-

Build worker power. Unions have been shown to reduce racial inequality and provide economic security for Black workers. California policymakers must repeal Prop 22, which misclassifies app-based drivers as independent contractors and prevents their access to basic labor protections. Legislation that empowers workers, such as AB3075 which holds employers more accountable for wage theft, should be strengthened and expanded to ensure that recessions are less catastrophic for low-wage workers. Finally, California must increase funding for enforcement of labor and employment laws while also making state financial support for businesses conditional based on compliance with those laws.

-

Create high-quality public jobs accessible to unemployed workers. A Federal Job Guarantee would ensure everyone has access to living-wage jobs while meeting the physical and care infrastructure needs of disinvested communities. Policymakers should take immediate steps to support unemployed workers through direct job creation in crucial sectors, like the Public Health Jobs Corp program proposed by President-elect Biden.

- Expand access to upskilling opportunities and stable career pathways. Policymakers should proactively connect unemployed workers to good jobs by investing in workforce development, including higher education and training programs that reach Black workers, and enacting community workforce agreements on state-funded projects. Programs such as California’s Breaking Barriers to Employment Initiative, which funds workforce development programs for those with barriers to employment, should be strengthened and expanded while business leaders should commit to advancing equitable employment practices and offering good job opportunities to workers hard-hit by the pandemic.

*The California Employment Development Department defines workforce as all individuals residing in California who worked at least one hour per month for a wage or salary, were self-employed, or worked at least 15 unpaid hours per month in a family business. Those who were on vacation or on other kinds of leave were also included.