The Bay Area’s Black Workers Face Multiple Barriers to Workforce Equity

The tech sector has spurred immense economic growth in the Bay Area over the past few decades, but not all workers have shared equally in that growth. The region’s Black workers, who have historically endured systemic underemployment, workplace discrimination, and occupational segregation, continue to face numerous disparities in their workplaces. Black residents, especially men, are more likely to be unemployed or find full-time work than the overall working-age population; the region’s higher-paying occupational fields have not meaningfully improved their underemployment of Black workers since the turn of the century; and Black workers face wage disparities across occupations and educational levels. Resolving these disparities requires lasting policy change alongside community and workplace organizing to ensure that all workers can share in the benefits of economic growth.

By Ezinne Nwankwo, Ryan Fukumori, and Alex Balcazar*

Introduction

The Bay Area is one of the nation’s economic powerhouses, but not all workers and families share equally in the region’s prosperity. This analysis is the third in our Black in the Bay Area series with a focus on the Bay Area’s Black workforce. While the region’s Black workers face a host of challenges in achieving economic equity, this piece focuses specifically on trends of occupational segregation, or the concentration of Black workers (and other workers of color) in the Bay Area’s lowest-paying jobs, and underrepresentation of Black workers in the region’s lucrative tech, finance, science, and other white-collar fields.

Analyzing occupational segregation is essential to address workforce equity issues for historically marginalized communities across the region. In order to ensure that all workers have access to fair-paying, steady jobs with decent working conditions, we need to understand which fields currently employ (and underemploy) Black workers, and how wage disparities within and across these occupational groups shape Black families’ economic well-being.

Current-day occupational segregation trends in the Bay Area are the result of decades-old exclusionary practices in employment, education, housing, and community development. Black Americans fleeing Jim Crow segregation in the mid-20th century found opportunities in essential Bay Area industries, especially defense, manufacturing, and transportation jobs during and after World War II. The desegregation of workplaces, schools, and neighborhoods supported a growing Black middle class in California, and many Black residents took advantage of the state’s prominent public colleges and universities, which were tuition-free until the late 1960s.

However, many more Black residents faced persistent structural discrimination and benefited far less from the Bay Area’s post-WWII economic boom. Many white families left newly integrated neighborhoods for the many suburban developments farther away from cities like San Francisco and Oakland, taking their spending power and tax dollars with them. This de facto segregation fueled decades of underinvestment in majority-Black communities and schools, especially as the deindustrialization of the regional manufacturing sector led to a rise in low-paying service sector jobs, and conservative politicians and voters significantly defunded the state’s public education systems in the 1960s and 1970s. Because these educational, employment, and housing disparities have persisted across generations, many Black community members have also been under-equipped to seize opportunities in the Bay Area’s 21st-century tech boom.

At the same time, Black workers have played major roles in many of the Bay Area’s workforce equity movements over the past century, from organized labor to new models of employment and business ownership. These struggles for fairness and dignity in the workplace have been essential to our region’s history, advancing new ideas, policies, and practices that have made work more just and equitable for all workers across the Bay Area.

The key findings are:

-

The Bay Area’s Black workers are systemically underemployed: Working-age Black adults continue to have lower rates of labor force participation, employment, and full-time work compared to the overall population.

-

Black women have higher rates of employment but earn less: Black women in the Bay Area are more likely to be employed than Black men but earn lower median wages than Black male workers and all women workers.

-

The region’s white-collar employers continue to have disproportionately small Black workforces: Black workers, including both US-born and immigrant workers, are largely underrepresented in the region’s highest-paying job fields, and these trends have persisted for decades.

-

Most Black workers in the region are paid less than their peers: Full-time Black workers earn lower median wages than workers overall, and pay gaps for Black workers get worse in higher-wage fields and among more highly educated residents.

Data and Methods

This analysis utilizes microdata from the 2022 5-Year American Community Survey (ACS), 2010 5-Year ACS, and 2000 Decennial Census for all nine Bay Area counties. The universe for this analysis is all residents between the ages of 25 and 64 who do not live in institutional group housing (e.g., assisted care homes, carceral facilities) and who are civilians (not armed forces members). While many people between the ages of 16 and 24 are part of the workforce, many are also in school, so omitting workers younger than 25 allows us to more accurately measure rates of college completion.

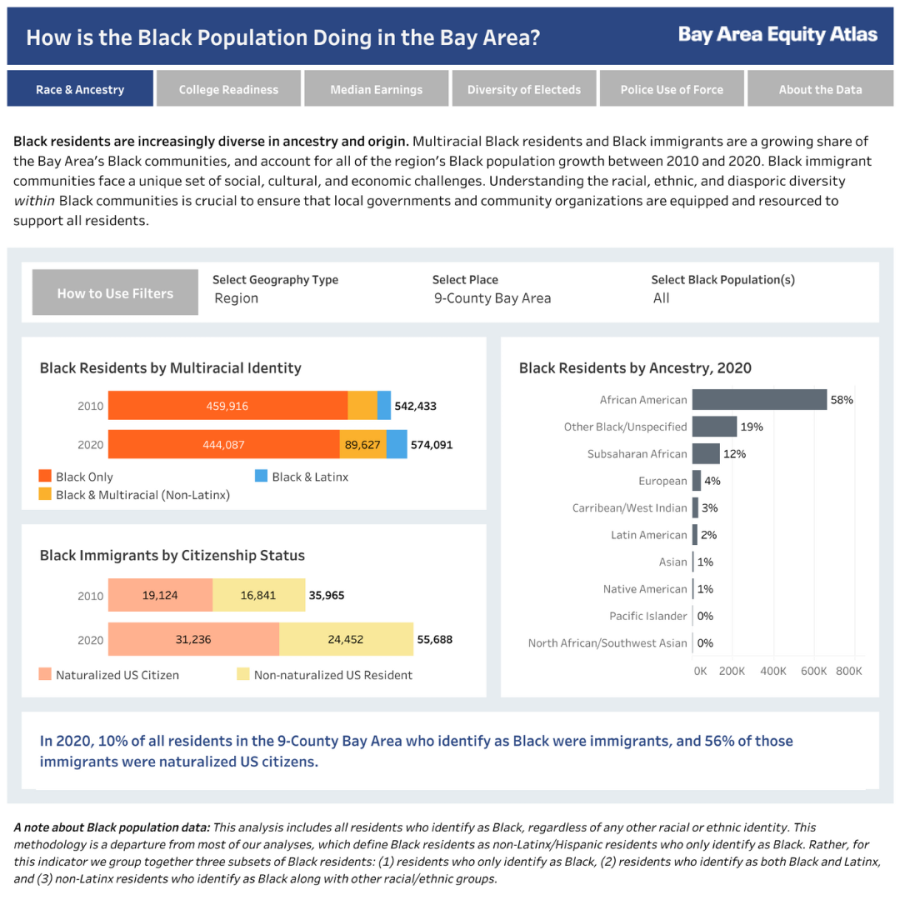

As with the first two analyses in the Black in the Bay Area series, this analysis includes all residents who identify as Black, including people who also identify as Latinx and/or other racial/ethnic identities. Most analyses on the Bay Area Equity Atlas enumerate Black residents as non-Latinx/Hispanic residents who only identify as Black. However, this series offers a more inclusive survey of the Bay Area’s Black residents, especially since multiracial Black residents have grown in number in recent years.

We cross-tabulate population data on race, ethnicity, and county of residence with data on:

- Gender (Individual question #2 on the ACS);

- Age (Individual question #3);

- Immigration and citizenship status (Individual question #7);

- Educational attainment (Individual question #10);

- Employment status the week prior to the time of survey (Individual questions #30, 36, 37);

- Number of weeks worked in the past 12 months (Individual question #40);

- Usual number of hours worked per week (Individual question #41);

- Occupation and job sector (Individual question #42); and

- Income from wage/salary work in the past 12 months (Individual question #43).

Some metrics in this analysis used specific criteria or methods:

- The majority of data figures in this analysis define employed residents as people who reported working at any time in the 12 months prior to the time of survey, regardless of their employment status at the time of survey. These criteria align employment status with earnings over the past 12 months, which allows us to calculate hourly wages.

- The figures that show labor force participation rate and employment rate consider employment status only at the time of survey, regardless of employment status over the previous 12 months. This alternative method was necessary because the American Community Survey only measures whether someone is part of the labor force at the time of survey, not historically. Without any knowledge of past labor force participation, it is impossible to calculate unemployment or labor force participation rates.

- We define full-time workers as people who reported working at least 50 out of the past 52 weeks (including holidays and paid time off) and worked an average of at least 35 hours per week. All other people who reported working in the past 12 months are counted as part-time workers.

- All median hourly wage figures are restricted to people who worked full-time over the 12 months prior to the time of survey.

- There are two ways to measure the Bay Area workforce using the American Community Survey: by tracking people who live in the Bay Area and tracking people who work in the Bay Area. The universe for this analysis is workers who live in the Bay, regardless of where they work. It is possible that we include some Black workers who live in the 9-County Bay Area but commute outside of the Bay Area for work. In addition, this analysis does not account for any Black workers who do not live in the Bay Area but commute into it for work.

As part of the research process, the authors also spoke to local policy experts, advocates, and community leaders engaged with Black workforce equity and labor rights in the Bay Area:

- Stasia Hansen, East Bay Alliance for a Sustainable Economy

- Louise Auerhahn, Working Partnerships USA

- Hope Williams, Sustainable Economies Law Center

- Savannah Hunter and Enrique Lopezlira, UC Berkeley Labor Center

- Clarence Sanon and Maurice Wilkins, solfood

Background and Context

In 2022, the 9-County Bay Area was home to about 237,000 Black adults ages 25 to 64 who had worked in the past year, about 6.7 percent of the region’s workforce. Black workers are concentrated in the East Bay: over one-third (37 percent) of the region’s Black workers reside in Alameda County, and over one-fifth (22 percent) live in Contra Costa County. In the two East Bay counties and Solano County, Black workers make up more than 10 percent of the county workforce. By contrast, Black workers represent a disproportionately low share of the workforce in the rest of the region, especially the rest of the North Bay (Marin, Napa, and Sonoma counties).

Slightly over 35,000 Black immigrants ages 25–64 are part of the Bay Area’s workforce, making up about 15 percent of the region’s Black workers and just under 1 percent of all workers. While the region’s Black immigrant population has surged in recent years, Black immigrants still form a relatively small part of the Bay Area’s immigrant population. Over 40 percent of the Bay Area’s working-age employed residents are immigrants, but only 2.5 percent of immigrant workers are Black. Across the region, 62 percent of Black immigrant workers are naturalized (obtained US citizenship), compared to 54 percent of all immigrant workers.1

While the Black immigrant worker populations are too small in most Bay Area counties to produce reliable estimates, data for the East Bay and South Bay reveals that Santa Clara County has a much higher share of immigrants among its Black workforce than other counties. Over one-quarter (26 percent) of Black workers in the South Bay are immigrants. However, because Santa Clara County attracts so many immigrant workers in general, Black immigrants only make up 2 percent of the local immigrant workforce, the same as their regionwide share of the immigrant workforce.

A smaller share of the Bay Area’s Black workforce has a bachelor’s degree or higher than the overall population, in no small part due to decades of public and private underinvestment in historically Black communities and their schools. Less than half (45 percent) of the region’s Black workers ages 25–64 have at least a bachelor’s degree, compared to 60 percent of all Bay Area workers in the same age group. The much smaller share of Black workers with a four-year college degree contributes to the disproportionately low number of Black workers in fields like medicine, science, and law, as the Key Findings will show.

At the same time, the share of Black working-age adults without a high school education is actually smaller than the share for all workers (4 percent vs. 7 percent). This may be explained by the relatively few Black residents among the Bay Area’s immigrant population, which has a higher share of adults without formal education than the US-born population.

The majority of this report examines occupational segregation for Black workers regardless of their job sector. However, it should be noted that Black workers comprise a disproportionately large share of the Bay Area’s public sector workforce at all levels. Black workers make up 10 percent of the state government employees who live in the Bay Area and 11 percent of local and federal government workers. Nearly 21 percent of all Black workers in the Bay Area work in some form of government, compared to 13 percent of all workers. The nonprofit sector also has a disproportionately high share of Black workers, while Black workers are underrepresented among the Bay Area’s private-sector companies and self-employed residents.

This concentration of Black government workers is neither a new trend nor unique to the Bay Area. For decades, public sector employment has been a reliable opportunity for many Black residents looking to build financial security and middle-class lives. Many government jobs are unionized, offering reliable steady employment, worker benefits, and retirement plans. However, this also means that Black workers across the country have been especially vulnerable to the widespread job cuts to the federal civil service under the second Trump Administration.

Key Findings

The Bay Area’s Black workers are systemically underemployed: Black adults continue to have lower rates of labor force participation, employment, and full-time work compared to the overall population.

As Dr. Steven C. Pitts notes in his historical study of Black workers in the Bay Area, structurally high unemployment and low wages have created multigenerational barriers for Black residents to achieve upward mobility and financial stability. While overall unemployment levels have been low outside of the COVID-19 pandemic, this systemic underutilization of Black workers is evident in regional workforce data. Labor force participation among Black working-age adults is lower than that of all working-age adults (79 percent vs. 83 percent). Although 93 percent of Black workers are employed, this figure is still three percentage points lower than the employment rate for all residents. Black workers are also less likely to be employed full-time than their counterparts (70 percent vs. 73 percent), and are thus less likely to enjoy the health-care coverage and other key benefits that are more available to most full-time workers.2

Labor force participation rates and full-time work rates have steadily improved for all Bay Area residents since 2000, and employment rates have rebounded since the Great Recession. However, Black residents in the Bay Area have consistently faced lower levels of labor force participation, employment, and full-time work relative to the overall population, whether in times of economic downturn or growth. Data from the Bay Area Equity Atlas also shows that Black workers endure some of the region’s highest unemployment rates and below-average labor force participation rates among major racial and ethnic groups, trends that have persisted for decades.

These disparities are found across the entire nine-county region, though there are some discrepancies between counties:

- In six of nine Bay Area counties, Black workers’ labor force participation rates fall within two percentage points of the labor force participation rate for all workers; only Alameda, Napa, and San Francisco have wider gaps. San Francisco has the largest disparity: although San Francisco has the highest rate of labor force participation among all Bay Area working-age residents (86 percent), only 71 percent of working-age Black residents are employed or looking for work.3

- Similarly, Black workers face higher levels of unemployment in nearly every Bay Area county. The gap is highest in San Francisco, where more than 10 percent of Black residents are unemployed compared to 5 percent of working adults. Only Napa, with the smallest Black population in the Bay Area, has an unemployment rate that is lower for Black workers (3 percent) than for all workers (5 percent).

- Black workers are employed full-time at lower rates than all workers in every part of the region except Marin and Sonoma counties, neither of which have substantive Black populations. The two counties spanning Silicon Valley make up the extremes for Black workers: Santa Clara County has the highest rate of full-time employment for Black workers (75 percent), while San Mateo County has the lowest rate (66 percent).

- The layered effects of unemployment and underemployment in Black communities are especially evident in San Francisco, where Black adults are substantially less likely to be part of the workforce, less likely to be employed, and less likely to have full-time work. These disparities add up, making it harder for households to maintain financial stability amidst increasingly higher costs of living.

Black women have higher rates of employment but earn less: Black women in the Bay Area are more likely to be employed than Black men but earn lower median wages than Black male workers and all women workers.

Breaking down labor force and employment rates by gender reveals that there are broader disparities between men and women in workforce participation, regardless of race. Working-age men have higher rates of labor force participation compared to working-age women (88 percent vs. 76 percent), and employed men are more likely to have full-time work (79 percent vs. 67 percent). However, employment rates are similar for both men and women, with 96 percent of those in the labor force employed.

Black women’s labor force participation and full-time employment rates track closely to that of all women, but there is a seven-point percentage gap between Black men and all men for those same metrics. Because Black men face a higher level of disparity compared to all men than Black women face compared to all women, the gaps in employment and full-time work between Black men and Black women are smaller than the gaps between all women and all men.

These disparities in labor force participation and full-time employment are in no small part because of the particular barriers Black men face. Due to the broader criminalization of poverty and Black people in the US, Black men experience higher rates of arrests and incarceration even for low-level offenses. Their unequal exposure to the criminal justice system can create significant barriers to employment. Black residents with carceral records often struggle to find and keep work, either because of employer discrimination, licensing restrictions that bar people with criminal records from occupational licensure, or criminal background checks that flag outdated or inaccurate records. As a result, higher levels of justice system involvement and overpolicing in Black communities can keep many community members, especially men, from securing stable employment and providing for themselves and their families.

In all, Black full-time workers earn a median hourly wage that is $10 less than the median hourly wage for all full-time workers ($32 vs. $42). While Black men are more likely to be unemployed than Black women, Black male full-time workers earn slightly higher wages than their female counterparts ($33 vs. $32). However, the gender wage gap for full-time Black workers is much less pronounced than the $8 median gender wage gap among all full-time workers in the region. Put differently, the median hourly wage gap between Black men and all men ($13) is much larger than the wage gap between Black women and all women ($6). This disparity follows a similar pattern to the wider gaps in labor force participation and full-time employment between Black men and all men.

Addressing disparities for employment and compensation among Black workers also requires addressing gender-based workforce disparities for all women, regardless of race. It is possible that women’s lower levels of labor force participation and full-time employment are a consequence of gendered norms that push mothers to contribute more of their time in unpaid domestic work, coupled with the unaffordability of childcare for many families. Black women contend with multiple forms of workplace malpractice, from gender wage gaps to systemic discrimination against all Black workers.

The region’s white-collar employers continue to have disproportionately small Black workforces: Black workers, including both US-born and immigrant workers, are largely underrepresented in the region’s highest-paying job fields, and these trends have persisted for decades.

Black residents make up 6.7 percent of Bay Area workers, but those workers are unevenly distributed across occupations. As the graph below shows, Black workers comprise at least 10 percent of the workforce in six occupational groups: protective services, transportation and material moving, health-care support, personal care and service, community and social services (including legal workers), and office and administrative support. While Black residents work as health-care practitioners at a share proportional to the overall workforce, other white-collar fields employ few Black workers, such as business management, the sciences, computing, and engineering. However, while Black workers make up sizable shares of some key service sector fields, they are relatively scarce in other major service fields, like food and restaurant industry jobs.

These disparities in employment for Black workers have persisted for generations. Black workers also made up 6.7 percent of the Bay Area workforce in 2000, near the start of the regional dot-com boom. The fields in which Black workers were both concentrated and underemployed have remained the same. Black workers made up at least 10 percent of the workforce in the same six occupational groups in 2000 and 2022.

Similarly, the distribution of all Black workers across occupations changed only slightly over these two decades. In both 2000 and 2022, the occupational group with the largest number of Black workers was office and administrative support, but the share of Black workers in those jobs decreased from 21 percent in 2000 to 13 percent in 2022. This decrease was offset by gradual increases of Black workers in other fields, including white-collar jobs like health-care practitioners and working-class occupations in personal care and service. However, the share of Black workers in any occupation besides office and administrative support did not change by more than three percentage points over this period.

This consistency in Black workers’ occupational segregation is notable, given how much the Bay Area’s economy transformed between 2000 and 2022 with the rise of Silicon Valley and the tech industry. Despite these changes, Black workers were employed in computing, math, and engineering jobs at the exact same rates in 2000 and 2022: 3 percent of all employees in these occupational groups, less than half of their overall share of the regional workforce. As of 2022, about 9 percent of all Bay Area workers ages 25-64 worked in computing and math jobs, compared to just 4 percent of Black workers. This suggests that the region’s tech employers have made little progress in addressing issues of institutional and workforce diversity over an entire generation, despite consistently higher rates of higher educational attainment for the region’s Black workers over this period.

Examining workforce trends for Black immigrants specifically brings up some key differences in occupational distribution that can get obscured in the larger population data. Black immigrants make up just 1 percent of Bay Area workers, while US-born Black workers make up about 6 percent. Unlike US-born Black workers, Black immigrants are relatively well-represented among health-care practitioners, technicians, and scientists, and are not concentrated in fields like office and clerical work, education, or sales. At the same time, Black immigrants and US-born Black workers are both disproportionately represented in some of the same service occupations like health-care support, protective service, transportation and warehousing, and personal care and service.

This data is consistent with broader trends showing that many immigrants from sub-Saharan Africa, who account for much of the Bay Area’s Black immigrant population, have higher levels of education and are more likely than other Black immigrant populations to migrate, having already earned an advanced degree. The majority of sub-Saharan African immigrants in the US migrated from countries where English is the official language or commonly spoken, which may offer some advantages in the US labor market. The Bay Area is not the only part of the US where Black immigrants make up a sizable portion of the health-care workforce.

While some highly educated Black immigrants enter higher-paying occupations like medicine, many, like their US-born Black counterparts, are concentrated in essential but often undervalued industries. Their degrees and credentials are often devalued, and many report being overqualified for their jobs relative to their skills and educational attainment. As a result, Black immigrants often earn lower wages and have limited access to health coverage and other employment-related benefits despite their much higher labor force participation rates.

In discussing occupational segregation, we do not suggest that the Bay Area’s highest-paying jobs are the most important. Black workers occupy significant shares of the essential industries that kept residents safe at the peak of the COVID-19 pandemic, staffing health-care centers, personal care services, community support agencies, and multiple workplaces in the supply chain. Even as some workforce advocates stress the importance of diversifying white-collar industries, it is all the more vital that every occupation provides livable wages and decent working conditions, including the fields where Black workers are already concentrated.

Most Black workers in the region are paid less than their peers: Full-time Black workers earn lower median wages than workers overall, and pay gaps for Black workers widen in higher-wage occupations and among more highly educated residents.

In 2022, the median wage for all working-age full-time workers in the Bay Area was $42 but just $32 for Black full-time workers. However, the wage gap between Black workers and all workers varies across communities and workplaces.

First, wage disparities vary by county. The median wage gap between Black workers and all workers varies between counties, and is largest in counties where overall median wages are highest, especially in Marin, San Francisco, and Santa Clara. By contrast, the wage gap is smallest in the two counties with the lowest overall median wages, Solano and Sonoma. This data is consistent with our earlier findings that Black workers are starkly underrepresented in many of the Bay Area’s high-paying occupational groups, which are common in the highest-income counties.

Wage disparities between Black workers and all workers also vary by occupation. As the graph below shows, Black workers make up larger shares of several occupational groups with the lowest median wages, especially personal care and service, transportation and material moving, and health-care support. The gap in median wages between health-care support workers and health-care practitioners and technicians ($24 vs. $56, a $32 difference), or between office and administrative workers and business managers ($28 vs. $61, a $33 difference) illustrates the stark class disparities that can exist between workers in the same industries.

For the large majority of occupational groups, Black workers have lower median wages than the overall median wage. These include nearly all occupations where Black workers are concentrated. Black workers make up over 21 percent of the region’s protective service workers, but earn a median wage $13 lower than the overall median ($25 vs. $38). There are a few occupations where Black workers earn higher median wages than workers overall, but these are mostly fields with small shares of Black workers, like construction, production and manufacturing, and building and grounds maintenance. Those are also fields that employ a relatively high number of undocumented workers, who are more likely to be underpaid, driving down overall median wages.

In general, the median wage gap between Black workers and all workers increases as the field’s overall median wage also grows. Computer and mathematical workers have the highest median hourly wage at $75, but Black workers in those roles earn a median wage $27 lower. Not only have the region’s Science, Technology, Engineering, and Mathematics (STEM) employers systemically underemployed Black workers for an entire generation, but they also pay their few Black workers much less than the overall workforce.

Wages in the Bay Area also vary by workers’ nativity. Black women and men earn lower median hourly wages than their counterparts, regardless of citizenship status. However, for Black workers, gender wage gaps vary across immigration statuses. There is no gender wage gap between US-born Black full-time workers, with both men and women making $32 an hour at the median. Among Black full-time workers who are naturalized immigrants, men have a median wage $9 higher than women’s wages, but among Black full-time workers who are noncitizens, the trends are reversed: women earn $3 more per hour than men at the median.

For Black immigrants, median wages are distinctly split between naturalized citizens and noncitizens. Median wages for Black naturalized male workers are significantly higher than wages for all Black men ($40 vs. $33), which overlaps with our earlier findings that Black immigrants are more proportionately employed in some of the region’s higher-wage industries. However, median wages for Black naturalized female workers are $1 lower than median hourly wages for all Black women ($32 vs. $31), indicating that employment opportunities for Black naturalized citizens are split across gender.

Of course, analyzing occupational groups and wages alone cannot capture the many challenges that Black immigrant workers face, even those who arrived in the US fluent in English. In addition to the challenges of social integration and inclusion, Black immigrants may contend with structural barriers in the labor market as a result of their race and immigration status. These challenges are consequential as they can suppress wages and limit access to high-paying jobs. Despite facing their own financial struggles, many Black immigrant workers must contend with the high cost of living in the region while also sending money, or remittances, to friends and relatives in their countries of origin. Although remittances support basic needs, contribute to the well-being of families and communities, and help sustain economies, recent policy proposals have called for imposing taxes and fees on remittances. Such measures could significantly reduce the amount of money that reaches families abroad and could increase financial pressure among Black immigrant workers in the region.

Lastly, wage gaps between Black workers and all workers vary by education levels. Since 2000, Black residents in the Bay Area have reached higher levels of educational attainment. In 2020, 31 percent of Black residents ages 25 and up had at least a bachelor’s degree, compared to just 19 percent in 2000.4 As is the case for all residents, median wages for Black workers rise alongside workers’ highest level of education: the median hourly wage for Black workers with a graduate degree ($49) is nearly twice the median wage for Black workers with a high school diploma and/or an associate’s degree ($26).

However, increasing levels of education have not helped to resolve wage disparities for Black workers as a whole. As Black workers gain additional education, they experience an ever-increasing wage gap between themselves and their educational peers. For workers between the ages of 25 and 64 with less than a high school diploma, Black workers’ median hourly wages are $1 higher than the overall median ($20 vs. $19). However, the wage gap reverses for workers with a high school diploma, some college experience, or an associate’s degree, with Black workers earning $2 less an hour at the median than all workers ($26 vs. $28). That wage gap rises to $11 for workers with a bachelor’s degree ($39 vs. $50) and $20 for workers with a master’s or professional degree ($49 vs. $69).

The large wage gaps at the higher ends of educational attainment may be explained in part by the occupational groups where Black workers are disproportionately clustered. Because Black workers make up larger shares of the workforce in education and community services, there may be a higher proportion of workers with graduate degrees in fields like social work, teaching, and the humanities than workers with STEM degrees. Nonetheless, given the increasingly high costs of higher education, Black people are more likely to have taken out more loans to finance their education. As a result, wage disparities can have long-term consequences for Black workers who may take longer to repay their student loan debt.

Taken together, our findings show that wage disparities between Black workers and all workers are the largest in the locations and fields where wages are the highest overall: in places like San Francisco, in occupations like tech and engineering, and for workers with graduate degrees. While it is critical to create equal access to the region’s most promising job markets and highest-earning jobs, it is clear that access alone is not enough to resolve these gaps. Much more is necessary to build an economy and governing institutions that ensure all workers have the resources, conditions, and opportunities they need to thrive.

Strategy in Action

Workers in East Oakland fight for a fair share of the Oakland Coliseum sale.

In the past few years, all three of Oakland’s major professional sports teams–basketball’s Warriors, football’s Raiders, and baseball’s Athletics (A’s)–left their longtime home stadiums in East Oakland for other cities. Meanwhile, the City of Oakland (which partially owns both the Oakland Arena and Oakland-Alameda County Coliseum) and Alameda County (which co-manages the complex on behalf of the A’s, who own the other half) have been in negotiations to sell the complex to the African American Sports & Entertainment Group (AASEG), a local Black-owned firm. The Oakland United Coalition, a group of East Oakland community organizations mobilized by the East Bay Alliance for a Sustainable Economy (EBASE), has been essential in advancing the interests and well-being of local community members at the negotiating table.

Photo credit: Joyce Xi. Retrieved from East Bay Alliance for a Sustainable Economy

Oakland United has organized to ensure that the eventual sale of the Coliseum complex to AASEG includes a comprehensive community benefits agreement (CBA). The Coliseum and Oakland Arena have long employed East Oakland residents, but these have included many jobs in low-paying service work, and stadium workers have suffered from the previous departures of professional teams. Coalition partners envision a CBA that includes good pay and benefits, consistent scheduling, and fair chance hiring for workers with justice system involvement, as well as minimum hiring requirements for workers in the most economically dispossessed zip codes in East Oakland. Additional construction projects on the site would require contracting with unionized firms. UNITE HERE, which represented many of the food service workers under the A’s tenure, is pushing for a first right of return for former workers who were laid off when the A’s left. In addition, the CBA would ensure that any housing development on the site includes at least 25 percent affordable units.

CBAs are an important strategy to provide a city’s existing low-income residents with a fair share of opportunities from new economic growth. For example, EBASE led a previous campaign to implement a CBA for local workers in the redevelopment of the former Oakland Army Base at the Oakland Ports. The fight for the CBA at the Coliseum is one part of Oakland United’s larger campaign to secure the equitable and environmentally sustainable redevelopment of the entire neighborhood, including the business corridor around the Coliseum and Oakland International Airport. Capital investments and market-rate housing development amidst the tech boom, combined with the underproduction of affordable housing, have helped to displace many residents from the city’s historic Black neighborhoods. The rapid departure of three major teams has further contributed to a fraying social fabric for longtime East Oakland residents. Organizers hope that a locally owned, revitalized Coliseum complex could renew the space as a focal gathering place for the community, while also offering good jobs and housing that empower local residents to share in the prosperity.

Recommendations

The following recommendations may help to improve employment-related outcomes for Black workers in the Bay Area.

Strengthen government oversight agencies that properly enforce civil rights and equal opportunity employment statutes, prevent worker exploitation, and regulate workplace-based discrimination. Historically, federal civil rights agencies like the Equal Employment Opportunity Commission (EEOC) and the Department of Justice (DOJ) Civil Rights Division have been essential in establishing nationwide protections for historically marginalized workers and litigating employer malpractice. State- and local-level agencies are also instrumental in enacting labor rights legislation and holding employers accountable to worker protections and civil rights standards.

However, under the second Trump Administration, EEOC and DOJ officials have indicated that they intend to use federal regulatory resources to punish or persecute employers with diversity, equity, and inclusion (DEI) initiatives. These shifts in practice threaten to undo decades of civil rights gains in the nation’s workplaces and federal agencies alike. A government that truly works for everyone must have enduring regulatory institutions at all levels of government bound to the Equal Protection Clause in the 14th Amendment and a commitment to ensuring fair outcomes for all workers regardless of race, gender, and other identities.

Enact a federal jobs guarantee. Despite the widespread financial challenges posed by the COVID-19 pandemic, the early part of the 2020s witnessed significant real wage growth for Black workers after decades of wage stagnation. This era of wage growth correlated strongly with high levels of employment. Black workers have historically faced heightened risks of cyclical unemployment in economic downturns, and the chronic underemployment of Black workers worsens racial income and wealth gaps. A federal jobs guarantee program, which would offer work at non-poverty wages to any adult who needs employment, can prevent unemployed workers from experiencing a financial crisis while advancing a wide range of civic improvement projects. A long-term state of full employment can also strengthen the job market for workers and protect wage gains for lower-income workers.

Index minimum wages to local median wages. Indexing wages to local median incomes helps wages keep pace with the Bay Area’s rising costs. According to the Washington Center for Equitable Growth, indexing the minimum wage to 50 percent of the local median wage would better align pay and earnings with local economic conditions.

Address the criminalization of poverty as a workforce equity issue. The criminalization of poverty disrupts opportunities for workers to maintain stable employment and income. Punitive local ordinances like those that sanction sleeping in vehicles or storing personal belongings in public spaces, among other similar laws, disproportionately target unhoused and low-income community members. These punitive measures can be especially harmful for Black residents who are already subject to overpolicing. In addition, many justice-involved workers reentering the labor market benefit from supportive services and inclusive employment practices. Such supports may include employer incentives to hire formerly incarcerated individuals, paid reentry training, and record expungement.

Invest in the creation and growth of Black worker centers. Black worker centers are community hubs that support and mobilize Black workers. These organizations serve as grassroots campaign incubators and policy shops, empowering local residents and workers to advocate for equitable workplaces, economic development, and policy change. As of the time of writing, local efforts are underway to revive the currently-defunct Bay Area Black Workers Center, which was once located in East Oakland.

Protect the right of workers to self-organize. When workers are unionized, they are more likely to receive equal pay, benefits, and workplace protections. Yet many workers face structural barriers when trying to organize. At the federal level, strengthening the National Labor Relations Board (NLRB) is essential for protecting workers’ right to organize. Similarly, state and local governments can enforce labor standards, especially in nontraditional employment, protect workers from discriminatory and retaliatory firings, and support sectoral bargaining and whistleblowers. Major employers can voluntarily recognize employee unions without NLRB intervention and engage in good-faith collective bargaining.

Expand and bolster pathways to quality jobs in sectors where Black workers have been historically underemployed. As our research shows, the Bay Area’s white-collar tech, science, and finance sectors have failed to meaningfully incorporate Black workers over the past generation of economic growth. Addressing the de facto segregation of the region’s workplaces requires a concerted effort from multiple parties, from workforce development agencies to employers themselves. Existing workforce training programs, like San Francisco’s TechSF program, offer pathways for young adults interested in technology careers. However, meaningful sectoral change requires employers to meaningfully address their own hiring and retention practices, including considerations for nontraditional training and experience, and rethink their norms around compensation and promotion.

Improve wages and working conditions where Black workers are already concentrated. While it is important to secure greater workforce equity in high-earning fields that currently underemploy Black workers, it is just as crucial to address conditions in occupations that do employ Black workers in larger numbers, like transportation and warehousing, protective service, health-care support, and personal care and service. These include many jobs essential to the Bay Area’s economy and communities, especially with an aging population that requires a wide range of health and home care services. However, these occupations are among the region’s lowest-paying jobs.

Labor unions in transportation, shipping, health care, and protective services can organize workplaces to enact living wage standards, ensure safe and healthy working environments, and implement predictable scheduling and other job quality standards. Strong policy and regulatory protections are necessary to safeguard the rights and well-being of domestic workers, many of whom face heightened risks of exploitation and abuse. Improved working conditions will benefit all members of the diverse workforces in these occupational groups.

Expand investment and entrepreneurship opportunities that support Black-led initiatives. The widespread underpresence of banking institutions in majority-Black neighborhoods creates additional barriers for aspiring Black business owners seeking investment capital for their ideas. Lending institutions can also expand access to flexible loan products to aspiring entrepreneurs in historically underbanked areas. Small business capital investment can help prevent displacement in historically Black communities, helping to maintain aging business corridors and employing local community members.

Support Black immigrant workers through workplace and community inclusion. Programs that help recently immigrated workers transfer their skills and training have served as effective models for both social integration and support in navigating the US labor market. The Welcome Back Initiative helps internationally trained health professionals reenter their fields in the US, and Upwardly Global helps immigrants and refugees restart their careers once they arrive. Employers may partner with immigrant-serving organizations to recruit workers and develop tailored career services. Additionally, employers would do well to recognize the training and credentials some Black immigrants obtain before migrating.

Incentivize employers across all sectors and industries to adopt equity-driven hiring and advancement practices. Such efforts may include broad, skills-based hiring, conducting regular pay equity audits, and eliminating ambiguous or biased evaluation criteria. Local governments can use tax incentives or workforce development grants to reward employers who meet set goals. Procurement and funding may also be conditioned on demonstrated equity practices in recruitment, hiring, retention, and leadership. To achieve these goals, employers can adopt measurable indicators, such as those outlined in the draft Business Standards for 21st Century Leadership, which provide businesses a roadmap to meaningfully advance equity, inclusion, and socially responsible business practices. These corporate performance standards can guide decision-making at all levels of business operations, from governance and leadership to organizational culture to corporate philanthropy.

Support parents and caregivers through expanded benefits and services. Many Black workers, as well as workers in general, balance paid work with caregiving responsibilities. Expanding access to affordable childcare, paid family leave, and flexible scheduling will support working parents and other caregivers. Strengthening the federal Child Tax Credit, such as by permanently codifying the expanded child tax benefits from the COVID-19 pandemic recovery, will help support all eligible families.

Authors

Ezinne Nwankwo, Postdoctoral Research Associate, USC Equity Research Institute

Ryan Fukumori, Senior Associate, PolicyLink

Alex Balcazar, Data Analyst, USC Equity Research Institute

Acknowledgments

We are profoundly grateful for the invaluable guidance and insights provided by many individuals and advisors throughout this research.

We extend our heartfelt thanks to the members of our Equity Campaign Leaders advisory committee and their colleagues who provided their expert feedback on our key findings and recommendations: Stasia Hansen of the East Bay Alliance for a Sustainable Economy and Louise Auerhahn of Working Partnerships USA. We are equally grateful to the advocates, researchers, and leaders from our wider Bay Area community networks who offered their insights and experiences: Hope Williams of the Sustainable Economies Law Center, Savannah Hunter and Enrique Lopezlira of the UC Berkeley Labor Center, and Clarence Sanon and Maurice Wilkins of solfood.

We also express our sincere appreciation to Jocelyn Corbett and Mahlet Getachew at PolicyLink, who contributed to the recommendations included in this analysis. Furthermore, we are thankful to Jennifer Tran at PolicyLink and Amanda Lawson for their editing, Michelle Huang at PolicyLink for managing online publication, and Edward-Michael Muña, formerly of the USC Equity Research Institute, for earlier project management efforts. Your collective efforts have been instrumental in shaping this research.

Endnotes

1 Bay Area Equity Atlas analysis of American Community Survey microdata from IPUMS USA.

2 Black workers’ higher representation in part-time work may reflect ongoing disparities in access to quality jobs but may also result from the rise of the gig economy. While gig work may offer some flexibility and supplemental income, it can reinforce economic vulnerabilities as it often lacks the stability, benefits, and protections associated with quality full-time work.

3 The city’s Black unemployment rates have been exceptionally high for over a decade, and a 2017 Brookings study showed that the city’s Black unemployment rate was one of the highest among major US cities. More research is necessary to determine the precise factors behind this disparity. However, it is possible that the previous waves of Black displacement from the city have left a smaller population with a greater share of residents living under extreme economic conditions in an increasingly expensive city. For instance, the homelessness rate for Black people in San Francisco is over six times higher than the overall rate. While many unhoused people are employed, housing instability can make it difficult for residents to find and keep jobs.

4 For these particular figures, “Black” refers to residents who only identify as Black and not as Latinx/Hispanic or any other racial/ethnic identities.