An Equitable Recovery Means Ensuring the Economic Security and Prosperity of All Workers, Especially those Hardest Hit by the Pandemic

Our new analysis highlights how communities of color and low-income communities not only suffered the greatest job losses, but are also most likely to be behind on rent.

By Jamila Henderson

The Covid-19 pandemic and economic shutdown brought about an unprecedented rise in unemployment in the Bay Area and across the country. While some people have returned to work, unemployment remains higher than pre-pandemic levels, and the economic burden of unemployment and lost wages continues to weigh on many families and their ability to pay rent and other necessities. This is especially true for the region’s most vulnerable residents who are disproportionately low-income people of color and immigrants (especially undocumented workers). Typical data sources used to report on the state of equity are often lagged by several years. This analysis addresses the current crisis by including recent indicators on the state of equitable recovery in the Bay Area region and across the state.

Latinx and Black Workers Face Greater Health and Economic Risks Working Essential Jobs During the Pandemic

The Covid-19 pandemic has revealed long-standing racial segregation within the regional workforce. Workers of color are overrepresented among essential occupations—such as grocery store workers, healthcare professionals, bus drivers, and janitors—placing them at far greater risk of exposure to the virus. Workers of color are also disproportionately represented in lower-wage jobs that are less likely to provide benefits like health insurance, paid sick and family leave, and disability insurance.

Black Workers, Women, and Workers with Less Education Suffered the Greatest Job Losses

The pandemic also brought about significant racial and gender inequities in unemployment as illustrated by research from the California Policy Lab. Women across the state face higher unemployment rates and have disproportionately left the labor force to assume childcare responsibilities. Between March 2020 and February 2021, one third of women in the labor force statewide applied for regular unemployment insurance, compared with 27 percent of men. About 40 percent of California’s Black workers filed for regular unemployment insurance during the pandemic, the highest rate of any group and more than one-and-a-half times the rate of White workers (24 percent). Virtually all Black workers in the state with no post-secondary education filed for regular unemployment insurance (95 percent).

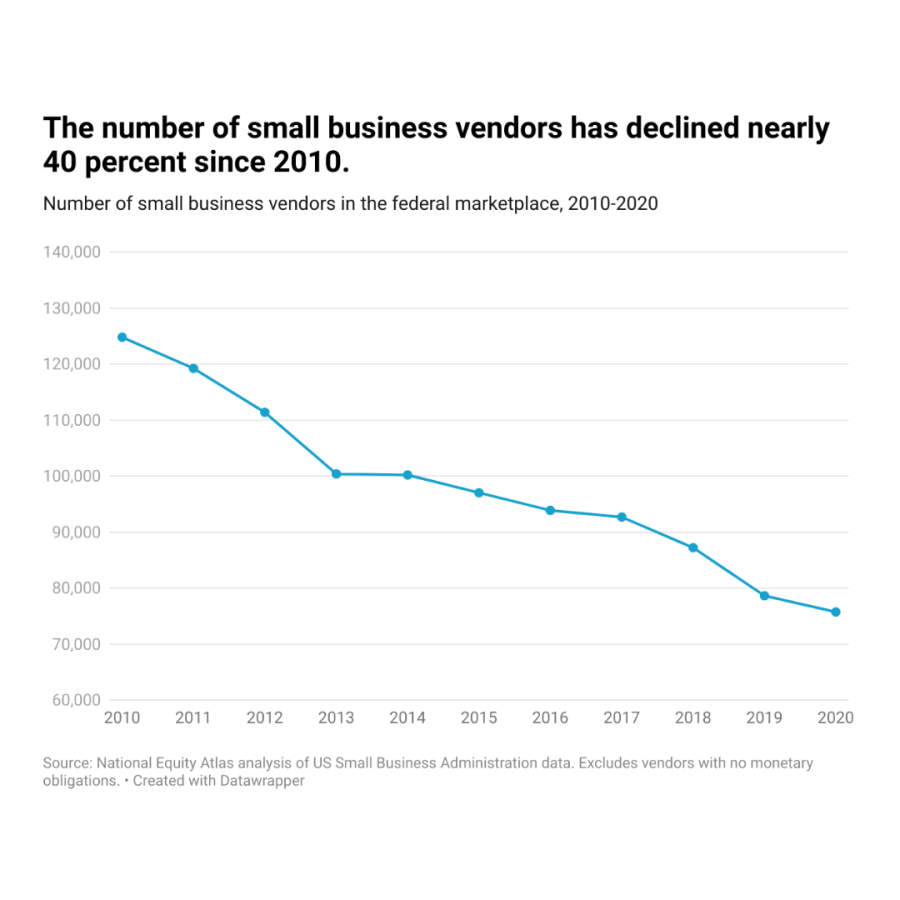

Bay Area PPP Loan Recipients Tend to be Large Employers, Leaving Small Businesses (Especially Those Owned by People of Color) Behind

An Associated Press analysis of Paycheck Protection Program (PPP) recipients across the nation revealed that businesses owned by people of color were last in line to receive PPP loans in 2020 because of barriers accessing the program’s banking institutions, or in some instances, multiple rejections or no response at all from banks. The analysis also showed that White business owners were more likely to secure loans early. Loan recipients in the Bay Area tended to be businesses with many employees, and most small businesses, especially those owned by Black, Latinx, Native American, and mixed-race owners, are single-person businesses with no additional employees.

Between January 2020 and February 2021, small business revenue across the region took a hit, and many businesses closed their doors permanently. Only Napa County saw an increase in small business revenue, but also a 25 percent drop in the number of businesses open. The decline was most severe in San Francisco, where only about half of businesses were open and revenues declined 56 percent.

Tenants Behind on Rent are Overwhelmingly Low-Wage Workers of Color Who’ve Suffered Job Losses During the Pandemic

The impact of the economic shutdown has been especially harsh for vulnerable renters. Facing job or income losses, most renters will do what it takes to pay their rent and keep a roof over their head, even if it means accumulating debt for other unpaid bills. Even so, it is inevitable that some of these renters will fall behind on rent without unemployment benefits and strong renter protections in place. People of color and low-income renters have been disproportionately impacted by the recession and are more likely to be behind on rent. 73 percent of those behind on rent earn less than $75,000 per year, and 70 percent are people of color.

The magnitude of the problem is great. An estimated 135,000 Bay Area households—12 percent of renter households are behind on rent. Absent strong worker and renter protections, they could face eviction and indebtedness. Collectively, these renters owe an estimated $747 million in rent debt, an average of over $5,500 per household behind on rent.

Economic Recovery Begins by Prioritizing Racial and Economic Equity

In the Bay Area, as elsewhere, the coronavirus and its economic fallout have disproportionately impacted the very same people who were on the economic margins before the pandemic, including Black, Latinx, and Native American residents, low-wage workers, and immigrant communities (especially undocumented workers). For the region to recover and thrive, policymakers must prioritize racial equity. This includes explicitly naming racial equity as a goal, prioritizing investments in historically underserved communities, building community ownership of land and housing, connecting unemployed and low-wage workers with good jobs, and supporting businesses owned by people of color and immigrants. Learn more here.